The development of microvascular surgery in Australia

Introduction

Participants

Beginnings

Developing links with academia and hospital medicine

A bevy of supporters

An ever-widening circle of contributors

Building research capacity

Nurturing relationships

Raising funds for research and development

The microsurgeon and the law

Winning community and corporate support

Leadership

The Institute and its style

Endnotes

Index

Search

Help

Contact us

Ann Westmore: Even that idea of the nylon thread coated with metal. Where would that have come from?

Sue McKay: That was Mr O'Brienís idea and it was constructed by a man called Mr Last.[89]

Ann Westmore: Prior to that what did they use?

Sue McKay: They didn't use anything because the article Iíve actually got talks about it being the first one.[90] Mr Last had spent many years and it had nearly driven him mad. Eventually they got these very fine needles. They also made the new style of micro-clamp, they got together on that.

Dick Bennett: I think the initial publications were by Bernard and his co-workers in the Department of Ophthalmology.[91] They were related to the instruments and techniques of microvascular surgery.

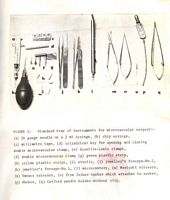

Early microsurgical instruments used at the Institute. Used with the permission of Dr David Fonda.

Phil Spry-Bailey: At lunchtime I was discussing with Wayne - because I went to China in 1972 just after the Whitlam Government sorted out our relations with China again and the Americans weren't allowed in then Ė and apparently Bernard went up there. I remember the Canton Trade Fair and a brochure which I brought home containing photos of a man who was involved in a train accident and they had sewn his left foot onto the right leg. I was surprised they were so advanced in 1972 and Wayne said, 'Yes, they were very good microsurgeons and they were well advancedí.

Bernard had been up there and came back and wrote a paper for the Medical Journal [of Australia] which was rejected. And the following year, the Americans were let in and someone wrote a similar paper and that was accepted, probably in an American Journal. But certainly, he was one of the first to get up there to recognise [how advanced the Chinese were], and he probably brought back some techniques as well, which the Chinese had. I might say that all this work that the Chinese had done to sew the foot back on was the work of Chairman Mao. (laughter)

Joan O'Brien: Professor Shen was the microsurgeon.[92] He and Bernard were working along the same lines without knowing each other. It was a fascinating trip for him [Bernard] and, on the social side, for me. Chairman Mao was still in control and everyone wore blue suits. When we went into a theatre, I realised I had the wrong clothes. I had a white suit and the whole theatre was blue. I stuck out like a sore thumb.

Maris Williams: Was that the Professor Shen who came out here? [93] He was such a sweet man.

Joan O'Brien: Yes, that was Professor Shen.

Laurence Muir: Don't you think to entrepreneur we should add pioneer in describing Bernard? Thatís the action of a genuine pioneer.

Sue McKay: I think when you mention that, I wonder if everyone here has read a book that Mr O'Brien wrote called Microvascular Reconstructive Surgery.[94] It contains a lot of the early history.

Laurie Muir: One of the greatest pleasures Bernard got was in winning students from America. He was always especially proud; fancy teaching the Americans!

Ken Knight: One of the interesting American Fellows was actually a Fellow with a Russian name, Bruce Shafiroff.[95] Bruce, and I think it might have been Wayne Morrison, were involved in producing an early logo (for the Institute) that had an Australian coat of arms with a kangaroo and an emu looking down an operating microscope focused on Melbourne.

|

Witness to the History of Australian Medicine |  |

© The University of Melbourne 2005-16

Published by eScholarship Research Centre, using the Web Academic Resource Publisher

http://witness.esrc.unimelb.edu.au/068.html