Tobacco Control: Australia's Role

Transcript of Witness Seminar

Introduction

Building the case for tobacco control

Producing, and Responding to, the Evidence

Campaigning for Tobacco Control

Economic Initiatives in Tobacco Control

The Radical Wing of Tobacco Control

Revolutionary Road

Tobacco Industry Strategies and Responses to Them

Campaign Evaluation

Managing Difficulties in Light of Community Consensus

Radical Wing Again

The Process of Political Change

Tobacco Campaigns Up Close

A Speedier Pace of Change

Political Needs and Campaign Strategies

Litigation and its Impacts

Insights from Tobacco Control

Tobacco Control in Australia in International Perspective

Appendix 1: Statement by Anne Jones

Endnotes

Index

Search

Help

Contact us

Terry Slevin: Thinking about that, one thing that’s become really clear to me more recently is that there’s a very conservative element of the non-government sector. We (in the health charity sector) still have to go out onto street corners and ask people for money, so there’s always a conservative leadership to ensure that we don’t go too far beyond public opinion.

Within that context of the tobacco world there was the real ratbag element, if you like, who were prepared to push the limit when it came to the issue of civil liberties and the like, and challenge the distance we would be prepared to go.

People like Arthur Chesterfield-Evans[105] and Brian McBride.[106] These were the guys who were prepared to say things.

I was working within government at the time. And since then, being in the non-government sector, it’s become clear to me that you have to get people who are very much out there on the edge prepared to float those ideas, and once they floated those ideas it opened up the position you could take from a broader concerned non-government sector which wasn’t on the very edge. Simon enjoyed that territory from time to time as well.

And so, in creating that kind of movement you’re able to move the argument along and bring the weight off the non-government sector, which allowed government to follow along behind. And I think that’s something worth hanging onto.

B.U.G.A. U.P., MOP UP[107] and ASH were certainly in that category.

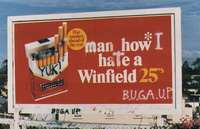

The radical wing of smoking control at work. Image courtesy of B.U.G.A. U.P.

Harley Stanton: Brian’s publication was Clean Air Clarion.

Simon Chapman: I have an anecdote that might illustrate Terry’s point.

About four years before the Sydney Olympics I was called into the office of the NSW Health Minister, Ron Phillips.[108] He said that he wanted me to pull together all the people in NSW who would support what was coming down the track, which was a ban on smoking in restaurants in NSW. This was being driven by (Bob) Carr,[109] who was a clean living kind of guy, and he was very, very keen for it to happen.

But Phillips named a couple of individuals - Arthur (Chesterfield-Evans) was one – who were not to be invited to the meeting.

I reflected on it and, of course, I told Arthur who found it highly amusing. But he said that the radicals had probably done a lot to push the agenda but they’d never been acknowledged when it happened. So I think in this case it’s very important we recognise them.

Dorothy Reading: But it’s also true that here in Victoria the Cancer Council consulted with and surveyed its constituency. It was important to know what people thought. And overwhelmingly people supported taking tough action on tobacco control.

So I do think in Victoria the leadership was from the Cancer Council in Victoria, I’m not sure about the situation in other states. David, you conducted those surveys and know how strongly our very large donor base supported tobacco reform.

David Hill: There was a lot of really good community support. And we were fortunate always to have very good boards (of management). Certainly, early on members of our board expressed concern to Nigel about going in hard on tobacco. That had to be dealt with. To Nigel it was a no-brainer.

But as soon as we did it, it became clear that enough of the public, anyway, thought it was the right thing to do. Incidentally I think, and this is guesswork admittedly, our donors would have noticed if we hadn’t done it, because as others have said, there was a lot of press about it and the public did know what was happening.

Simon Chapman: Ron mentioned earlier some groups saying, ‘You tobacco people, you’re running with money and we knew that we weren’t.’

What we were running with was great access to ‘unearned media’, a terrible expression that’s currently in use, which basically means advocacy, getting the headlines. Mel (Wakefield) has documented a lot of this in case study fashion longitudinally, looking at the sheer volume of articles in the press.

Garry Egger: Going back to Terry’s point, a lot was on-the-edge stuff. One of the most successful campaigns I’ve ever seen which wasn’t a campaign happened when Bill Snow threatened to dump a truckload of cigarette butts into Sydney Harbour because he said they were going to wind up there anyway. He never intended to do it, but it was front page of the Sydney Morning Herald the next day, which was a Saturday.

That drew immediate public reaction. It was enormous. You couldn’t identify yourself with it. But I think you’re right in saying you’ve got to have those people out there on the edge doing and saying these things, then conservative views follow on behind it.

Terry Slevin: Some people took big risks in their own chosen professions.

In sport, for example, a guy by the name of Wayne Pearce[110] who was a lauded Rugby League player in Sydney and a toiler who played for Balmain and became the captain of the Kangaroos, took a stand against taking the tobacco-sponsored player of the year award because he didn’t smoke, and he was a professional athlete. At the time, Rugby League, up hill and down dale, was sponsored by tobacco. He took a principled stand and really threatened his livelihood in so doing.

I remember a number of examples, he was one that stuck in my mind when I was working in NSW in the mid-1990s. There were others as well. Peter Sterling [111] did a similar kind of thing. We quickly tried to print posters of these individuals so that kids could put them on their bedroom walls and the like. There was a lot of pushback from rugby league. Those kinds of debates placed the tobacco industry in the ‘bad guy’ category.

|

Witness to the History of Australian Medicine |  |

© The University of Melbourne 2005-16

Published by eScholarship Research Centre, using the Web Academic Resource Publisher

http://witness.esrc.unimelb.edu.au/145.html